29 July 2020

This posting is a brief excerpt of my third article on public health priorities, on funding for the US CDC.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC) is the largest player in the disease control world. The US CDC’s total annual budget for federal FY20 was $7.9 billion, or 0.04% of the country’s US $21.7 trillion (T) GDP and 0.2% of its US $4.9T federal budget. By comparison, the World Health Organization’s 2019 budget was US $2.2B.

The US CDC spends approximately 11% of its budget on infectious disease identification and response and 59% on “regular” diseases, such as #NCDs, #HIV, birth defects and injury prevention.

How should the funding pie be split?

Cost drivers

One way to answer these policy questions analytically is to look at health care spending. If the major drivers of health costs can be better managed, then more funds will be available for other health (and non-health) services.

According to the US CDC, chronic and mental health conditions account for 90% of the $3.5 trillion (T) in annual health care spending. Chronic diseases include heart disease, lung diseases, stroke, diabetes, kidney disease, as well as cancer and Alzheimer’s Diseases and Related Disorders (ADRD). To the extent chronic diseases are preventable, then money spent changing people’s behavior (including to stop smoking, eat healthier, exercise more, use sunscreen and drink less alcohol) will see a good return on investment (ROI). Yet only 16% of the US CDC’s budget in FY20 is for chronic disease prevention. See Figure 4.

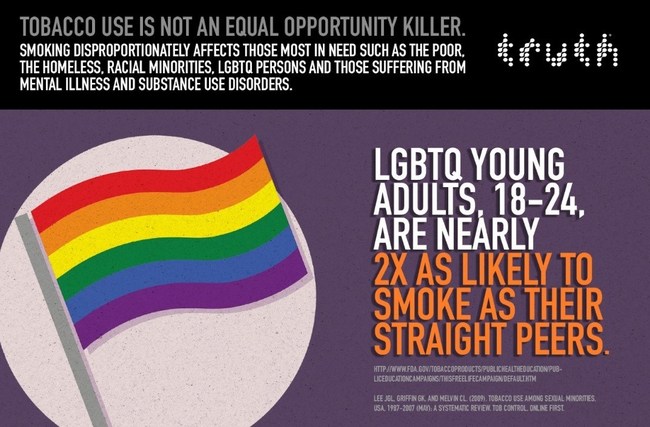

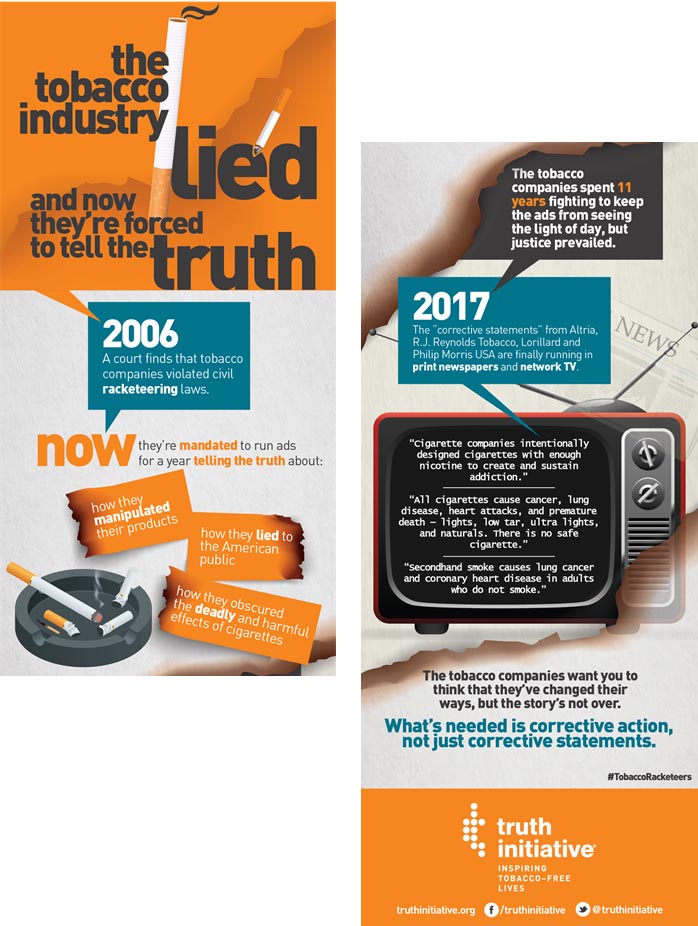

But motivating behavior change is hard. The truth campaign has been effective in reaching teenagers through anti-smoking ads. Community Health Workers (#CHWs) are another effective strategy in convincing people to adopt healthier behaviors and adhere to treatment regimens.

Underfunding

Is the US CDC underfunded?

Figure 6 shows the US CDC budgets for FY10, FY15 and FY20. Although the total budgets for FY10 (US $8.3 B, in FY20 $) and FY20 (US $7.9 B) are not so different, funding gaps and program shortages are chronic. A few examples:

- In 2016, to combat the spread of the virus Zika, which is particularly dangerous to pregnant women and their fetuses, the US CDC re-allocated $44 M intended for local health departments for emergencies such as hurricanes and the flu. The funds were transferred after Congress refused to allocate $1.9 B in emergency funding as requested by President Obama. While the funding transfer enabled the CDC to respond to Zika, at the same time it weakened local health departments.

- The US CDC’s Division of Oral Health (FY20 budget of $19.5 M) provides competitive grants to states for oral health prevention, including for surveillance infrastructure, water fluoridation and medical-dental integration. In 2018 only 20 out of 45 states that applied for funding received it, while 20 states have never been funded at all.

The overall pandemic-related funding has decreased 17% from FY10 to FY20 (see Figure 7).

What is the “right” amount of funding to spend on identifying, preventing, and responding to infectious disease epidemics? By contrast, how much money “should” be spent preventing chronic, long-term diseases that bring long-term health costs?

There are no easy answers.

#CDC #chronicdisease #HIV #publichealth #underfunding

Interesting. Who is overseeing CDC? How is CDC evaluating their effectiveness?

Hi Hannah

Thanks for your questions.

The CDC is part of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), whose Secretary is appointed by the president.

The CDC has evaluation strategies for different diseases and programs, but those are usually not well known. You may find relevant information at: https://www.cdc.gov/DataStatistics/, such as HealthyPeople 2020