Taken from my article on social determinants of health:

Sicker people cost more in health care resources. How do we equitably pay for their care? It would be immoral (not to mention illegal in many places) to charge people premiums based on their actual costs. One solution is using risk adjustment so payments reflect costs more closely; risk adjustment (RA) can be used by the government (paying insurers) or by an insurance company (paying medical providers).

In Switzerland, mandatory health insurance (MHI/Grundversicherung) companies with higher-risk members receive money from a fund paid into by companies with lower-risk populations. However, the risk adjustment calculation used to redistribute the money is based on only a few factors: age, gender, stays in a hospital or nursing facility and pharmaceutical cost group (PCG) for issues such as diabetes, depression, and cancer.

There is another set of factors that impact a person’s health care costs and health outcomes: social determinants of health (SDH).

Health is impacted by several inter-related drivers, each of which can have a positive or negative (or neutral) effect. A person’s biology (genes), access to medical care and lifestyle choices obviously help determine their health status. But so do their physical environments and social/economic characteristics, or SDHs, such as education level, employment opportunities, access to needed services and housing security. For example, it’s easier to maintain a healthy diet when fresh fruits and vegetables are both available in your local market and are affordable.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has made SDHs a key focus area to improve health equity worldwide. The University of Bern’s Institute for Social and Preventive Medicine (ISPM) social determinant research on young men found differences in the health behaviors of people from the Swiss, French, and Italian-speaking parts of Switzerland. Around the world, government agencies, private insurers, accountable care organizations (ACOs) and even individual medical practices are beginning to include social determinants of health in their assessments of patients.

In America, the state of Massachusetts’ public health insurance agency, MassHealth, began incorporating SDHs into their risk adjustment strategy in 2016. The formula to include SDHs includes unstable housing, disability, relationships with other state agencies, serious mental illness (SMI), and substance use disorders.

The Swiss Smarter Healthcare National Research Programme (74 NRP), part of the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), is also funding new research into the social inequalities in the provision of in-patient care. The research study aims to link medical and socio-economic data so that determinants can be identified regarding use of inpatient care for chronic diseases as well as health outcomes.

Of course, using SDHs is not necessarily a cure, as researchers recently found, to their surprise. As reported in the New England Journal of Medicine, a hospital program that sent a team of nurses, social workers and community health workers to “superutilizers” after their discharge resulted in a hospital readmission rate not statistically different from that of the control group.

Nevertheless, SDHs are a powerful tool to address underlying causes of people’s health problems. By capturing and using social determinant data, medical providers have the opportunity to improve their patients’ health and quality of life. When health care costs consequently decrease, that is an even better win-win outcome.

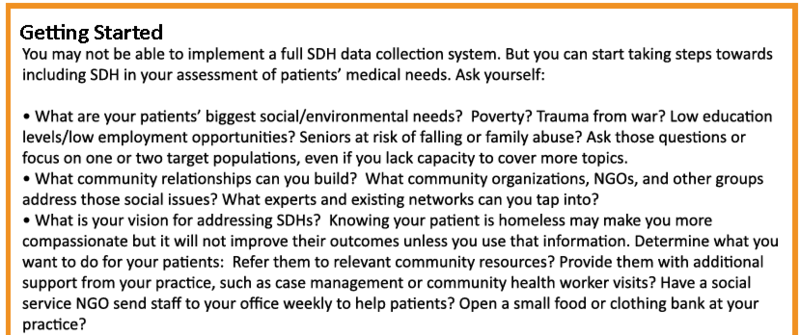

For more details, including examples of SDH use by health care providers and how to incorporate SDHs into your practice, read the full article on social determinants of health.

Fascinating, how the Swiss system “Grundversicherung” seems to be working well for everyone. Free competitions among insurance companies, free choice for the inhabitants, but then risk-adjustments in the background, so every market player can survive and prosper.